Everything happens at a particular time, right?

That armadillo fell from the sky at 3:48pm and... 17 seconds.

Whether you’re thinking in terms of Newton’s absolute space and time or Einstein’s relative space-time, time is a measure of what happens when.

Right?

Wrong.

Time ain’t what you think it is.

It’s far stranger – and far simpler – than you imagine.

Cosmic clocks

What is time?

Well, that’s easy.

There’s a giant clock in the sky.

Everything that happens in the universe happens at a particular time according to that giant clock.

Right?

Well, not quite.

Einstein’s theories of relativity insist that there’s no giant clock in the sky.

Time is relative.

Each reference frame has its own tiny clock.

Everything that happens in that reference frame happens at a particular time according to that tiny clock.

Right?

Well, again, not quite.

There’s no tiny clock in each and every reference frame.

There are no clocks at all outside the universe.

Time ain’t what you think it is.

It’s not an absolute scale along which we can measure what happens when in an absolute sense.

Nor is it a proliferation of relative scales along which we can measure what happens when in a relative sense.

Time isn’t extrinsic to our universe.

Time emerges from our universe.

Here’s how.

Time trap

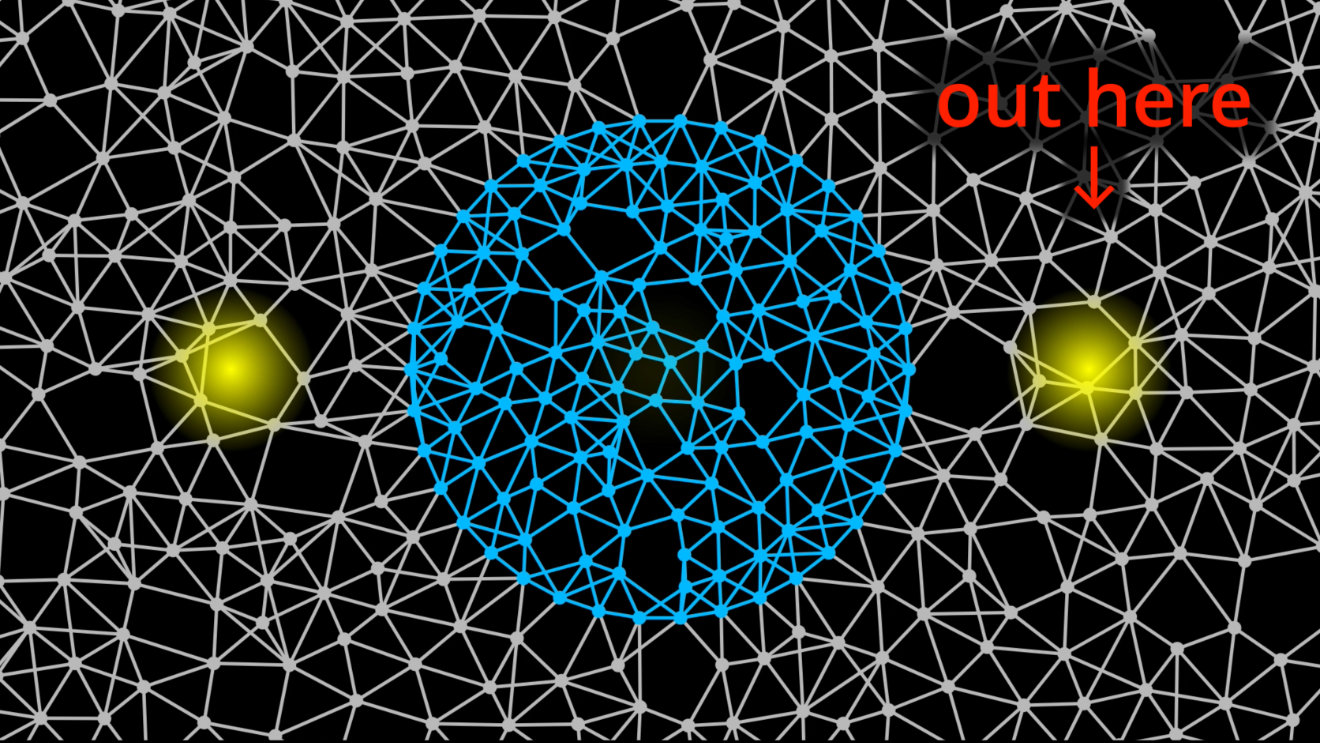

According to the Wolfram model, the universe is a hypergraph of nodes and edges.

The hypergraph is space.

Rules are repeatedly applied to the hypergraph...

...deleting some of the nodes and edges and creating others.

The evolution of the hypergraph is time.

So that’s a pretty straightforward answer to the question what is time?

According to the Wolfram model, time is the application of rules to the nodes and edges of the hypergraph.

So that’s it. That’s what time is. We’re done here. Right?

Well, once again, not quite.

This concept of time – the idea that it ticks forward with every application of a rule to the hypergraph – holds a trap.

It’s the same trap as we’ve had to avoid in thinking about space. Just as the hypergraph isn’t in space, it is space, so the evolution of the hypergraph doesn’t happen in time, it is time.

Let me show you what I mean.

Timekeepers

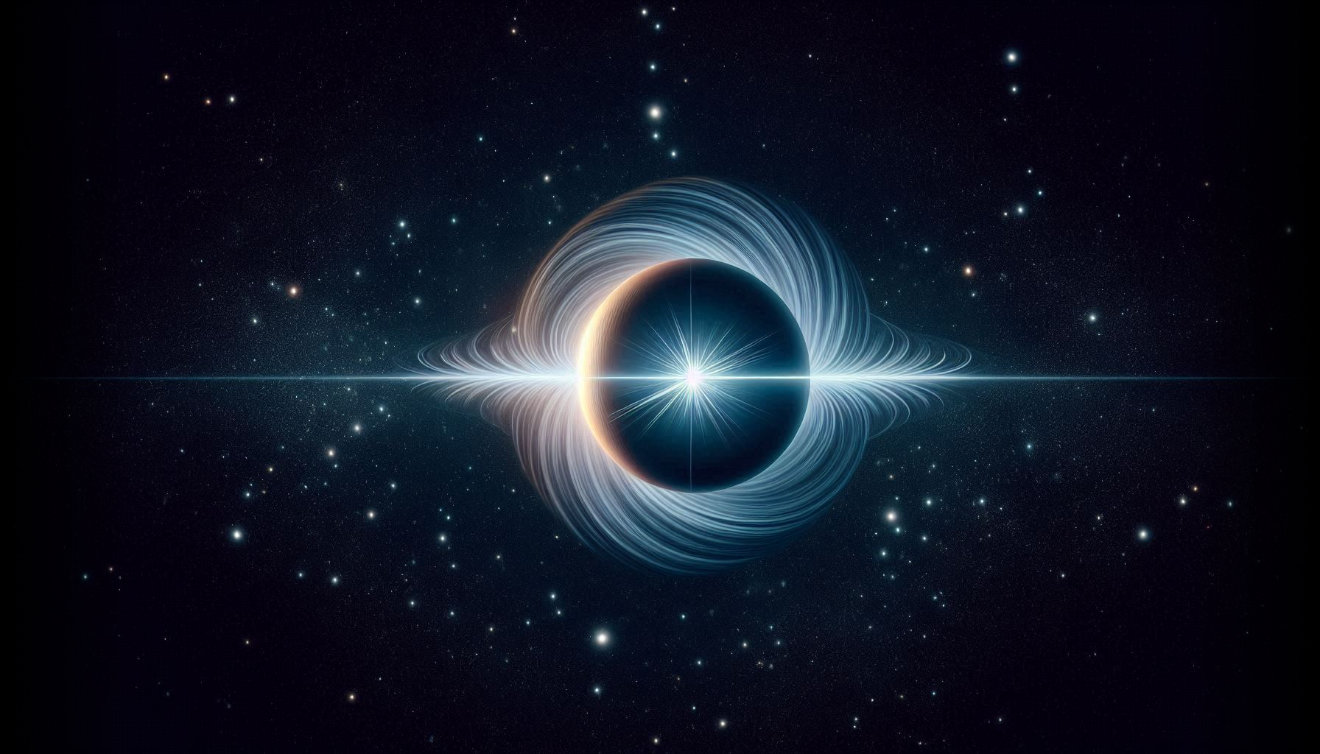

Let’s start with a pulsar.

It’s good to think about pulsars when we’re thinking about time, because pulsars are good at keeping time.

A pulsar is a spinning neutron star that sends beams of radiation out across the universe from its magnetic poles. If the stars align, then there’s a moment in every spin cycle when the beams from the pulsar light up the Earth. If it spins once every second, then, from the Earth, we’ll see a pulse once every second.

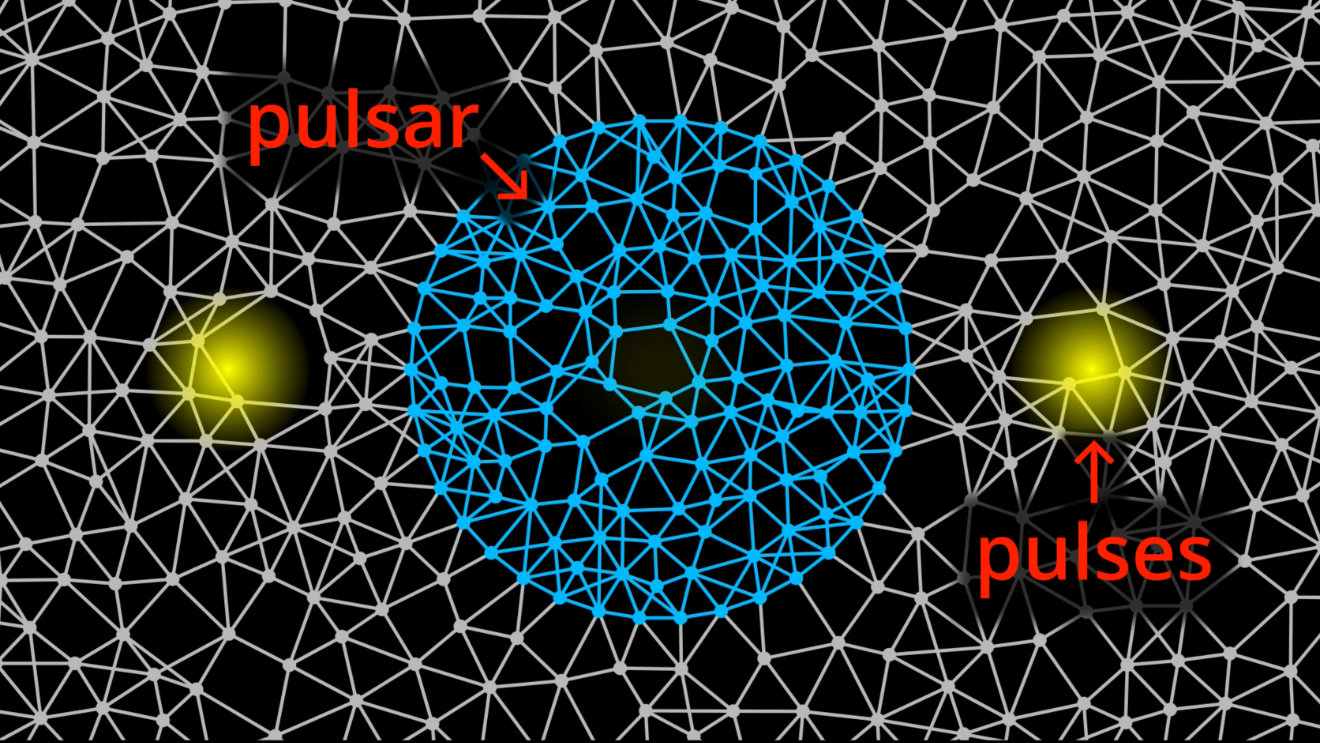

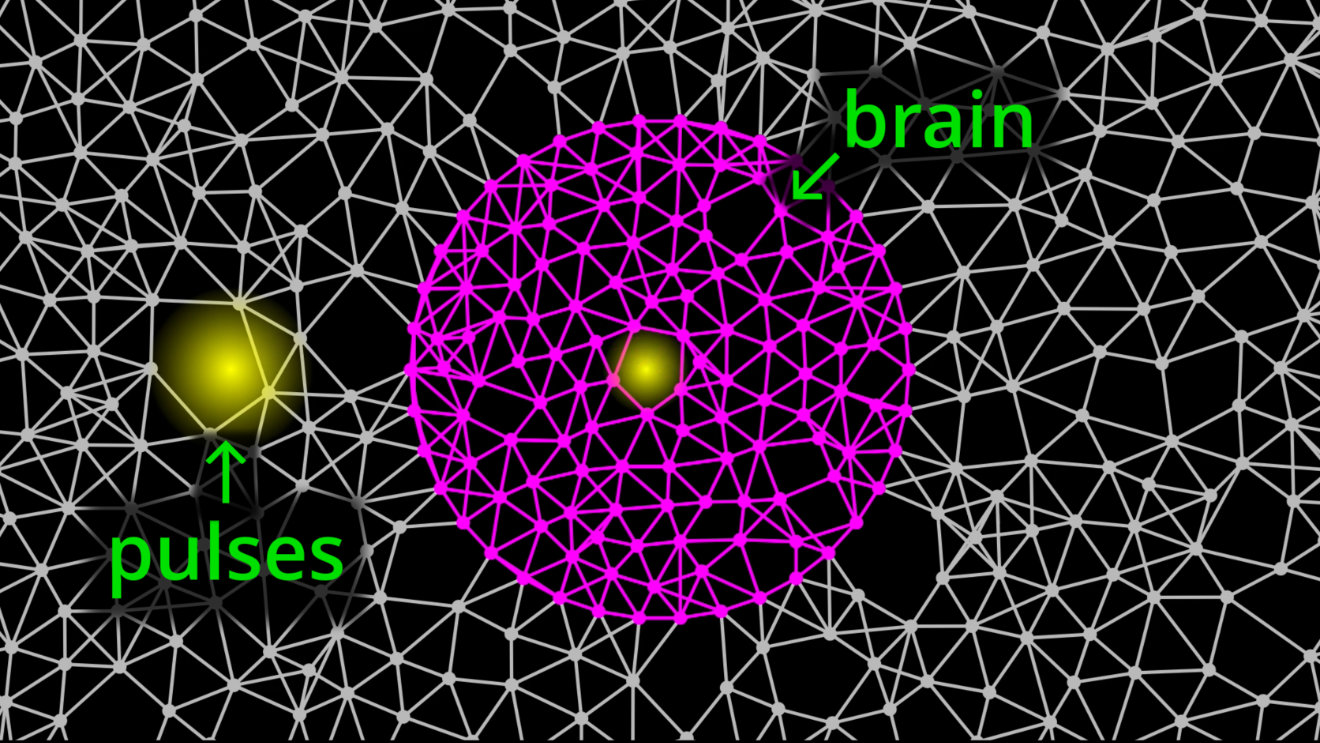

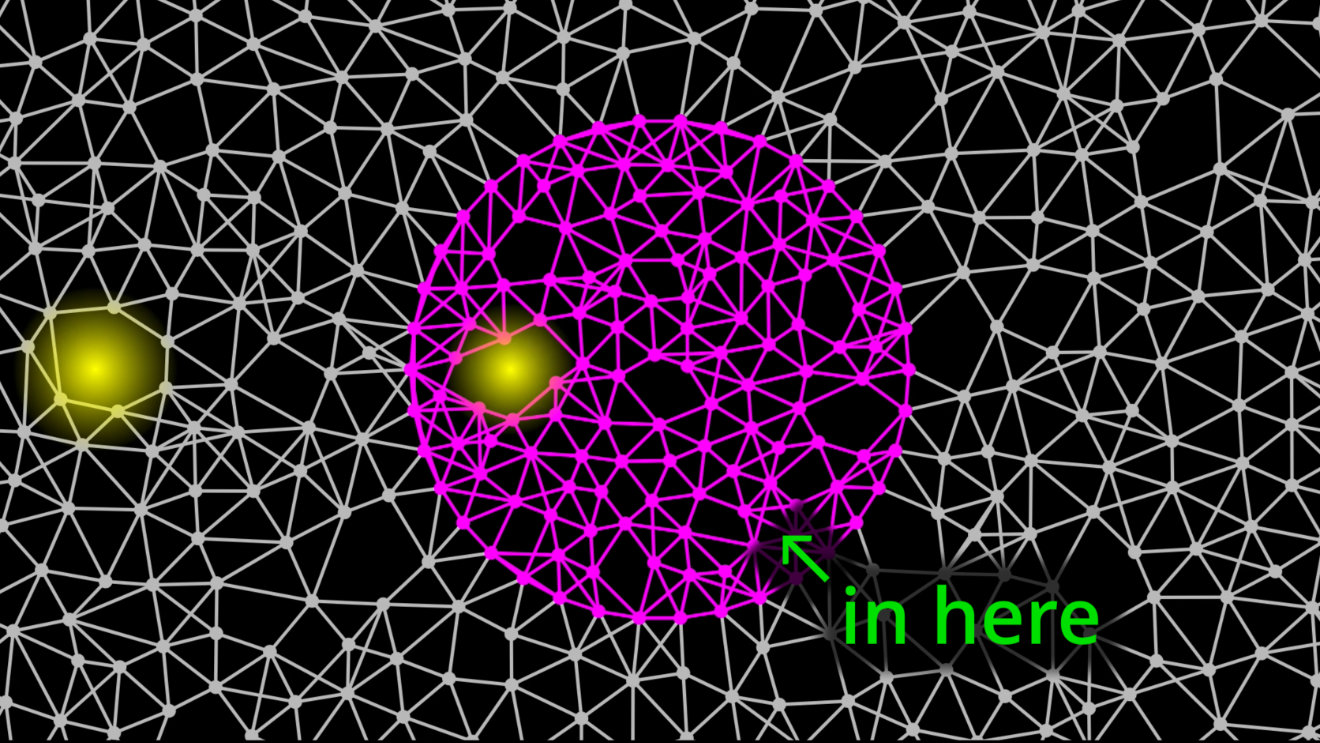

Here’s a somewhat simplified visualization of a pulsar in the hypergraph:

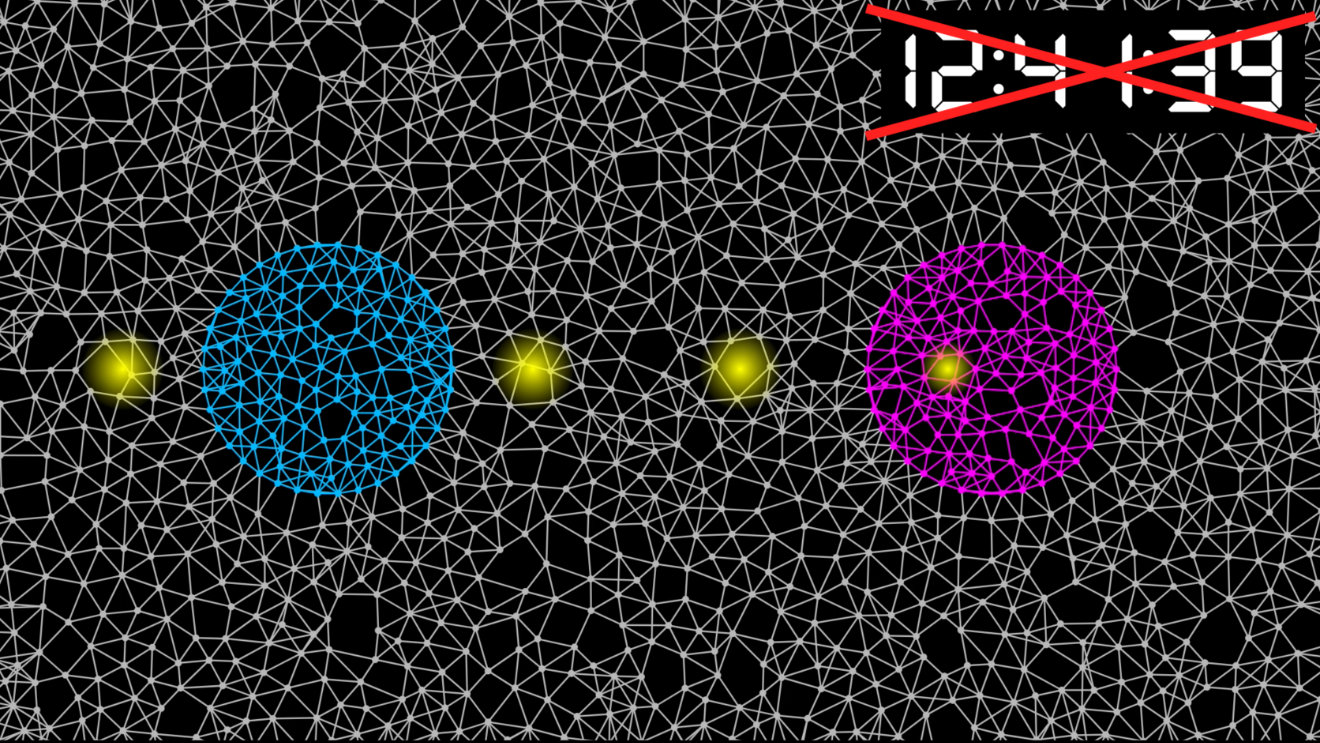

OK, some disclaimers here.

Obviously, this is not really how a pulsar would look in the hypergraph.

For a start, pulsars are quite big. There are maybe 1057 neutrons in a neutron star. We have no idea how many nodes and edges are involved in the persistent tangle in the hypergraph we call a neutron. Maybe 100, maybe 10100, probably somewhere in between. And let’s not even think about how many nodes and edges are involved in the spaces between neutrons, insofar as they exist in a neutron star.

Whatever the numbers, at the most extreme low estimate, there must be 1060 nodes and edges in a pulsar.

I’ve drawn... 600.

This isn’t a somewhat simplified visualization of a pulsar in the hypergraph, it’s an _astronomically over-_simplified visualization of a pulsar in the hypergraph.

And that’s just the numbers. Not only is this visualization of the hypergraph 60 or more orders of magnitude too small, it’s also too regular and, well, too fake.

I’m showing a hypergraph that’s highly regular and more or less two-dimensional, whereas the real hypergraph is likely to be highly chaotic and more or less three-dimensional, from a human perspective, at least.

Worse, I’m not really applying rules to the hypergraph in this visualization, I’m just faking it, rewriting selected nodes and edges to make it look like this is a pulsar emitting pulses of radiation.

And the colours – the blue of the neutron star and the yellow of the pulses – and the boundaries – the stable circle of nodes around the neutron star – I’ve just added those to make it clearer what’s going on. There are no colours or boundaries in the real hypergraph.

No matter.

For our purposes – for getting some serious insights into the nature of time – this fake hypergraph will do just fine.

It gets the fundamentals right.

Applying rules to the nodes and edges inside the pulsar causes the tangles of nodes and edges that make up those 1057 neutrons to propagate through the hypergraph according to the laws of physics, giving rise to the extraordinary phenomenon of a star heavier than the sun spinning at a rate of once every second.

Applying rules to the nodes and edges outside the pulsar causes the beams of radiation from its magnetic poles to propagate through space, maybe even as far as the Earth, where they’ll be observed through our radio telescopes as a pulse once every second.

It’s an astronomical over-simplification, but this visualization of a pulsar tells a true story: applying rules to the hypergraph causes pulses of persistent tangles of nodes and edges to propagate through the hypergraph, all the way from the pulsar to the Earth.

Breaking the pulsar-brain barrier

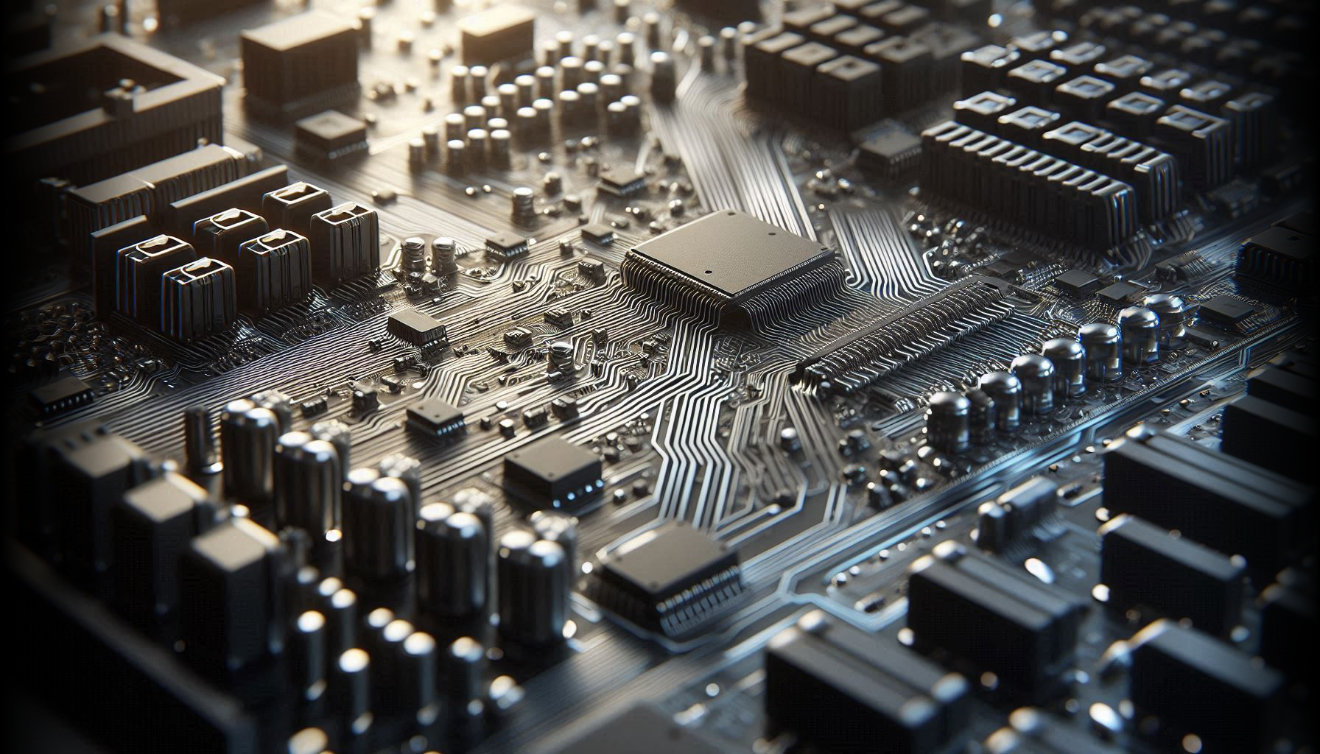

Let’s imagine that when they reach the Earth, an astronomer sees these pulses.

I mean, the pulses are going to have to go through a lot before the astronomer sees them.

From the pulsar:

they’re going to have to traverse light-years of empty space:

they’re going to have to be focused by the dish of a radio telescope:

they’re going to have to trigger the detectors at the focus of the radio telescope:

the signals from these detectors are going to have to be processed by a computer:

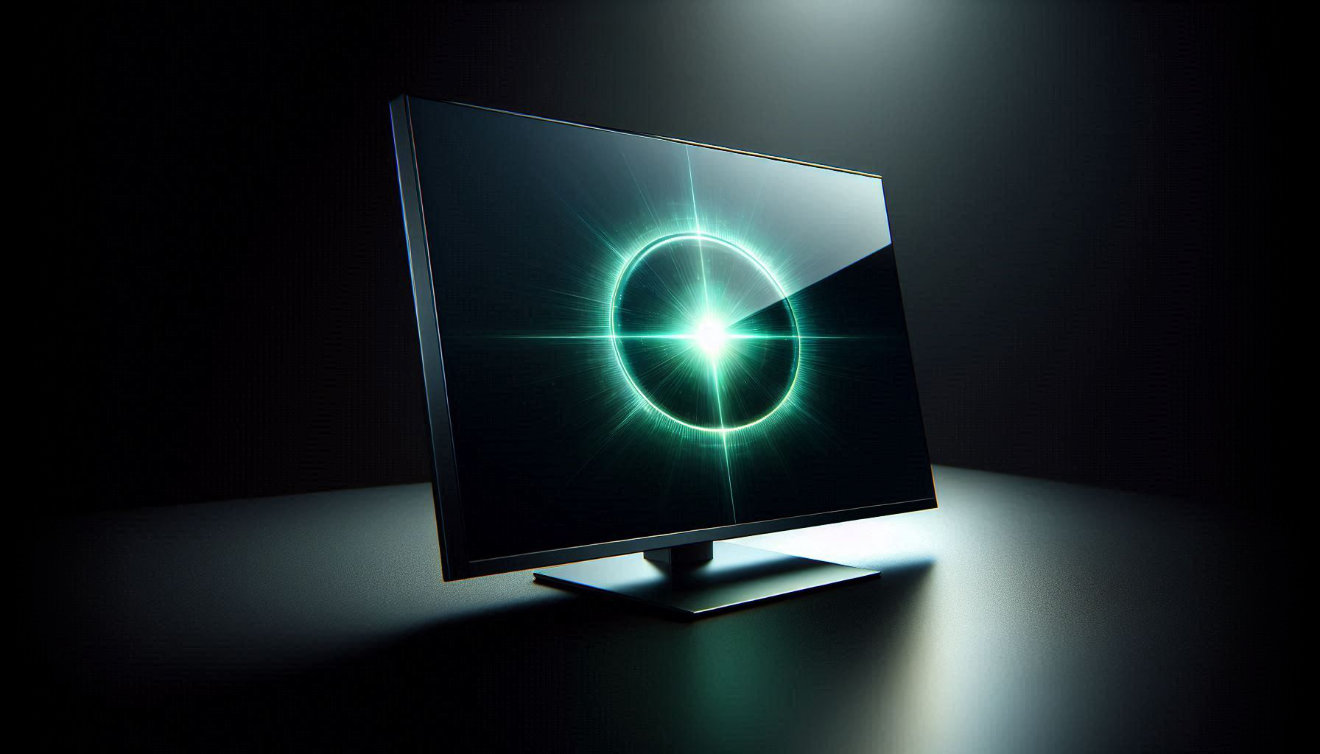

the resulting image is going to have to be displayed on a screen:

photons from the screen are going to have to traverse the light-nanoseconds of atmosphere between the screen and the astronomer’s eyes:

receptors in her retinas are going to have to trigger the firing of neurons in her optic nerves:

and the signals from these neurons are going to have to be processed by her brain into a perception of the pulses:

As you’ve probably guessed, I’m not going to be bothered by this immense complexity.

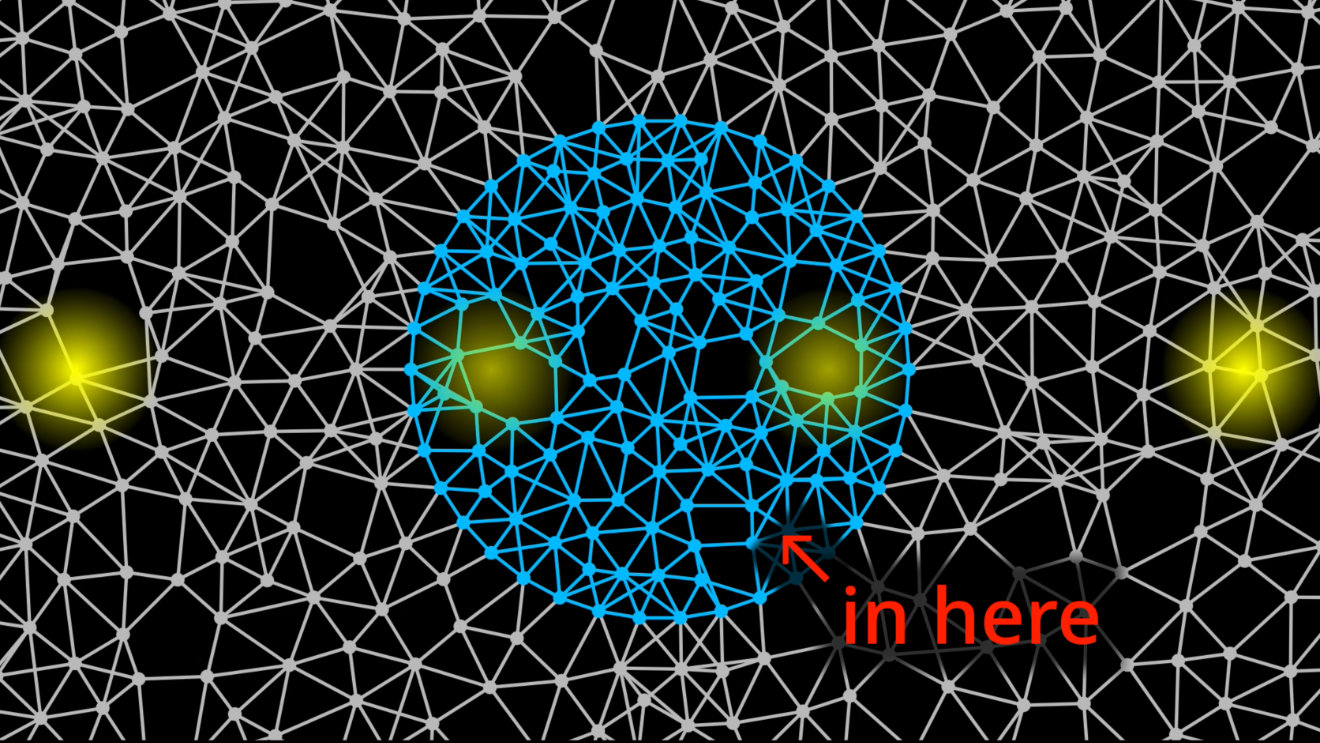

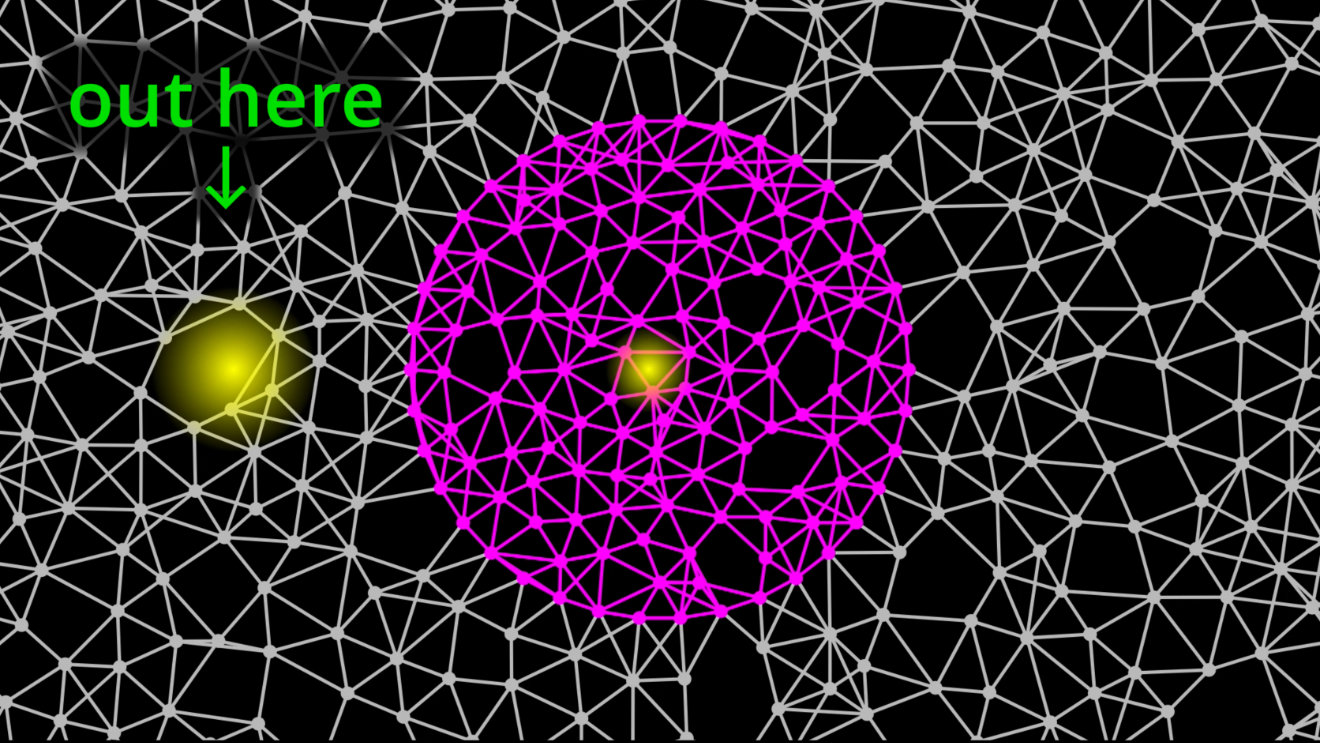

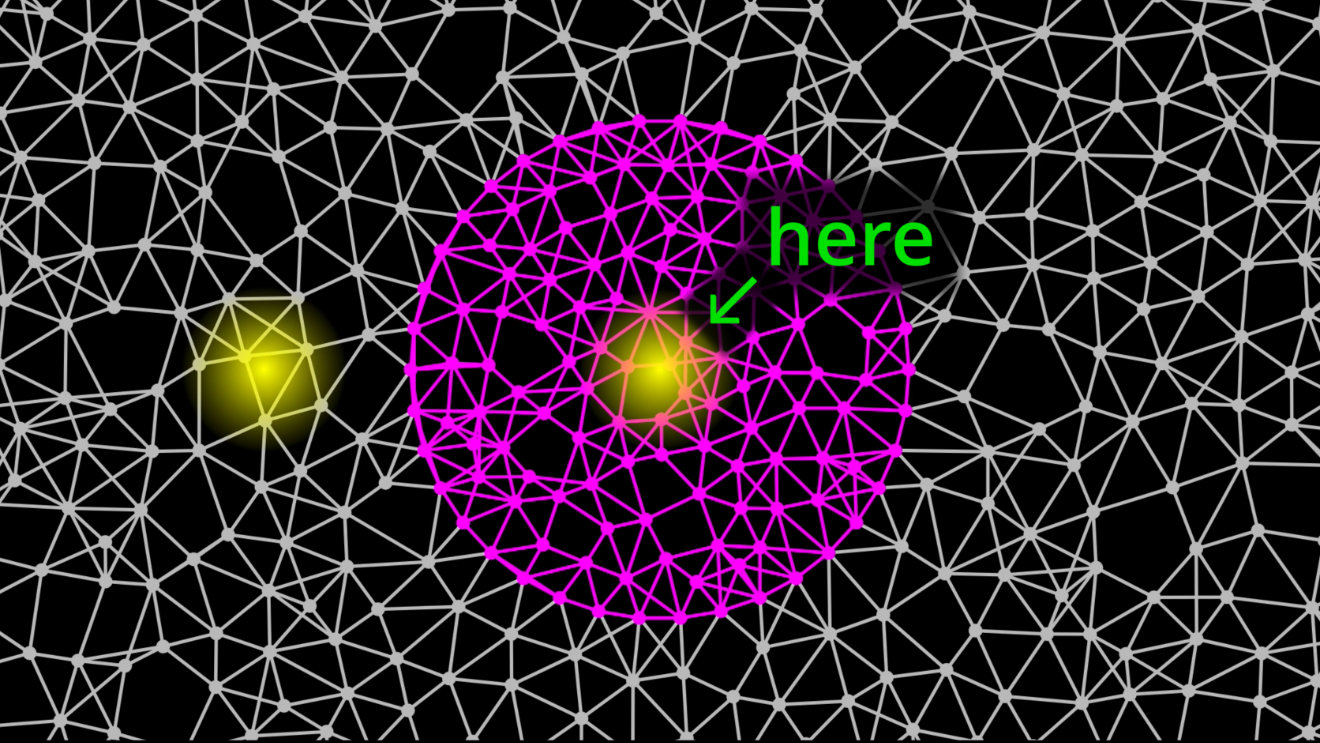

Here’s a somewhat simplified visualization of the astronomer’s brain in the hypergraph:

(Astronomers’ brains are round, right? And... purple.)

Regardless, this fake hypergraph gets the fundamentals right.

Applying rules to the nodes and edges outside the astronomer’s brain causes the tangles of nodes and edges that make up the photons from the radio telescope’s computer screen to propagate through the hypergraph according to the laws of physics, giving rise to the extraordinary phenomenon of light entering her eyes.

Applying rules to the nodes and edges inside the astronomer’s brain causes the electrical impulses from the receptors in her retinas to propagate from neuron to neuron...

...processing the information into the firing of a few neurons here, in the medial temporal lobe of her brain, correlated with her concept of a pulse from a pulsar.

Again, it’s an astronomical over-_simplification, but this visualization of the astronomer’s brain tells a _true story: applying rules to the hypergraph causes pulses of persistent tangles of nodes and edges to propagate through the hypergraph, all the way from the radio telescope to the medial temporal lobe of her brain.

Time flies

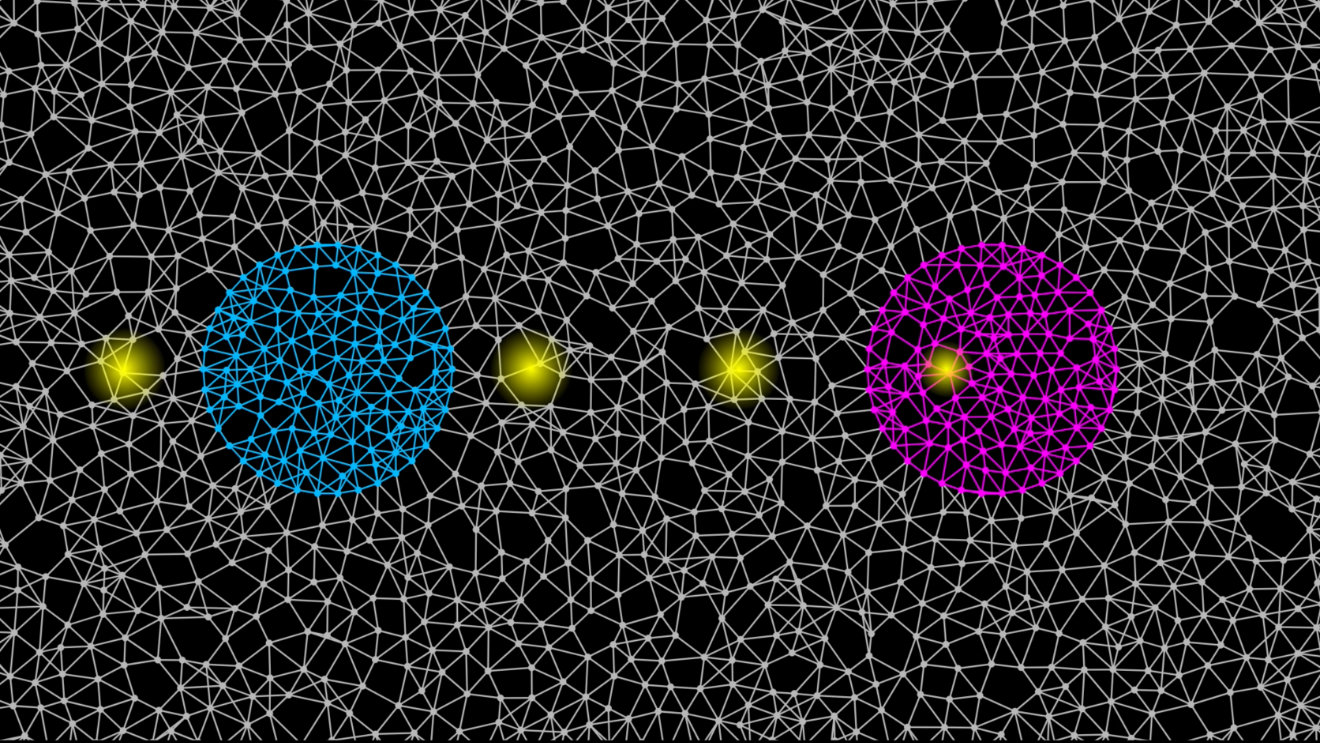

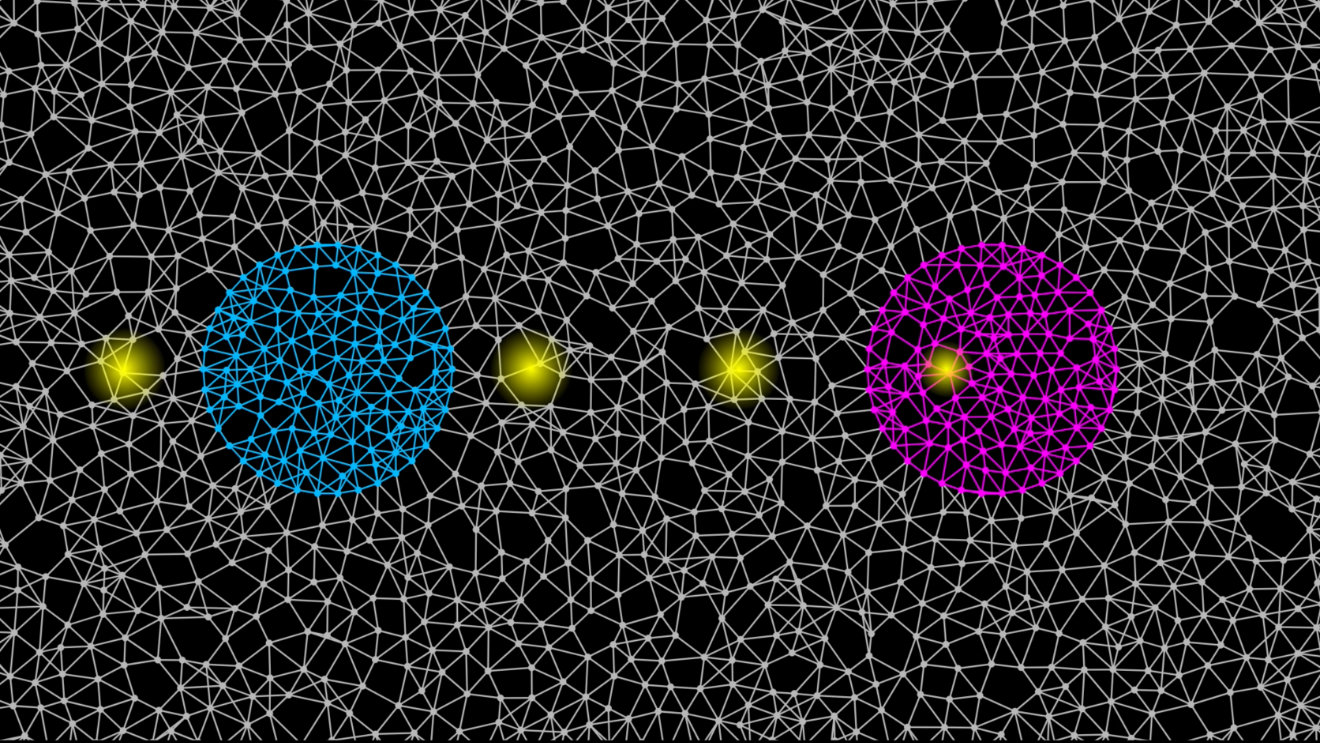

Let’s put these two visualizations together to get a more complete picture of the astronomer’s observation of the pulsar:

Now we can get those serious insights into the nature of time.

For a start, you can see how the application of rules to the nodes and edges of the hypergraph is time.

If I stop applying the rules, time stops. The pulsar stops pulsing, the beams of radiation stop propagating through space, and the astronomer’s brain stops processing the photons from the radio telescope’s computer screen into her perception of pulses. Indeed, the astronomer stops thinking completely.

If I apply the rules twice as fast, time appears to progress at twice the speed.

But this is an illusion.

Remember I said that the evolution of the hypergraph doesn’t happen in time, it is time?

Well, the confusion here is that I’m showing the evolution of the hypergraph in time.

I’m showing the hypergraph in space – the space occupied by the screen you’re looking at right now – and I’m showing the evolution of the hypergraph in time – the time it’s taking you to read this article.

In my defence, I really don’t have any choice but to show you the hypergraph in space, because space is where I live, and where you live, too. And I really don’t have any choice but to show you the evolution of the hypergraph in time, because time is how I evolve, and how you evolve, too.

But the real hypergraph – the one that is the universe – isn’t in space. It is space, and everything in it.

And the evolution of the real hypergraph – the one that is the universe – doesn’t happen in time. It is time.

Here’s a way to wrap your head around this.

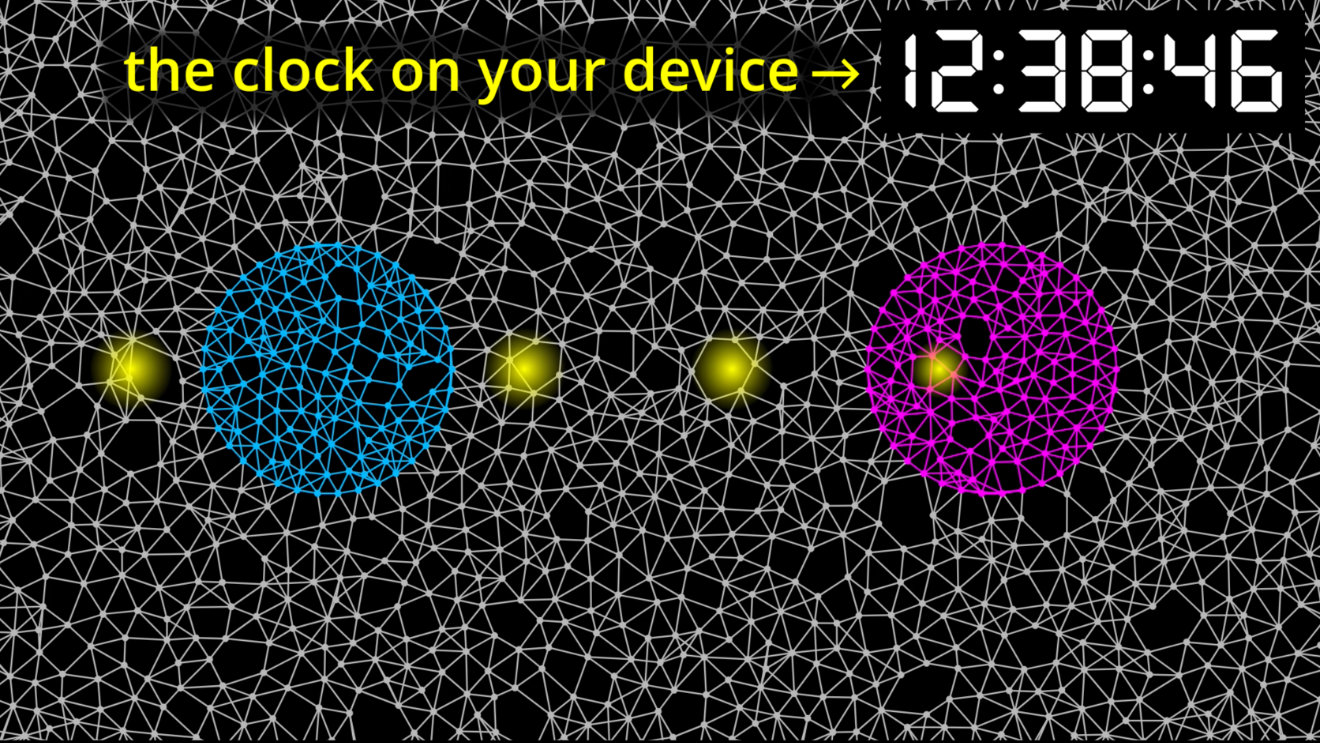

When, in my visualization, I apply the rules twice as fast, as measured by the clock on your device, for the astronomer, as an observer in the universe – inside the hypergraph – nothing changed.

The pulsar pulses twice as fast, as measured by the clock on your device.

The beams of radiation propagate twice as fast through space, as measured by the clock on your device.

The astronomer’s brain processes the photons from the radio telescope’s computer screen twice as fast, as measured by the clock on your device.

But the astronomer doesn’t perceive the pulsar as pulsing twice as fast.

How could she?

All she has to measure the frequency of the pulses is her experience of time. But it’s not just the speed of the pulses that’s doubled, from your God’s-eye perpective. The speed of the astronomer’s brain, too, has doubled, from your God’s-eye perpective, because her brain is in the hypergraph, just like the pulsar.

If I apply the rules twice as fast, from your God’s-eye perpective, the speed of the pulses doubles, but the astronomer’s experience of time doubles, too, so from her perspective, inside the hypergraph, the frequency of the pulses doesn’t change.

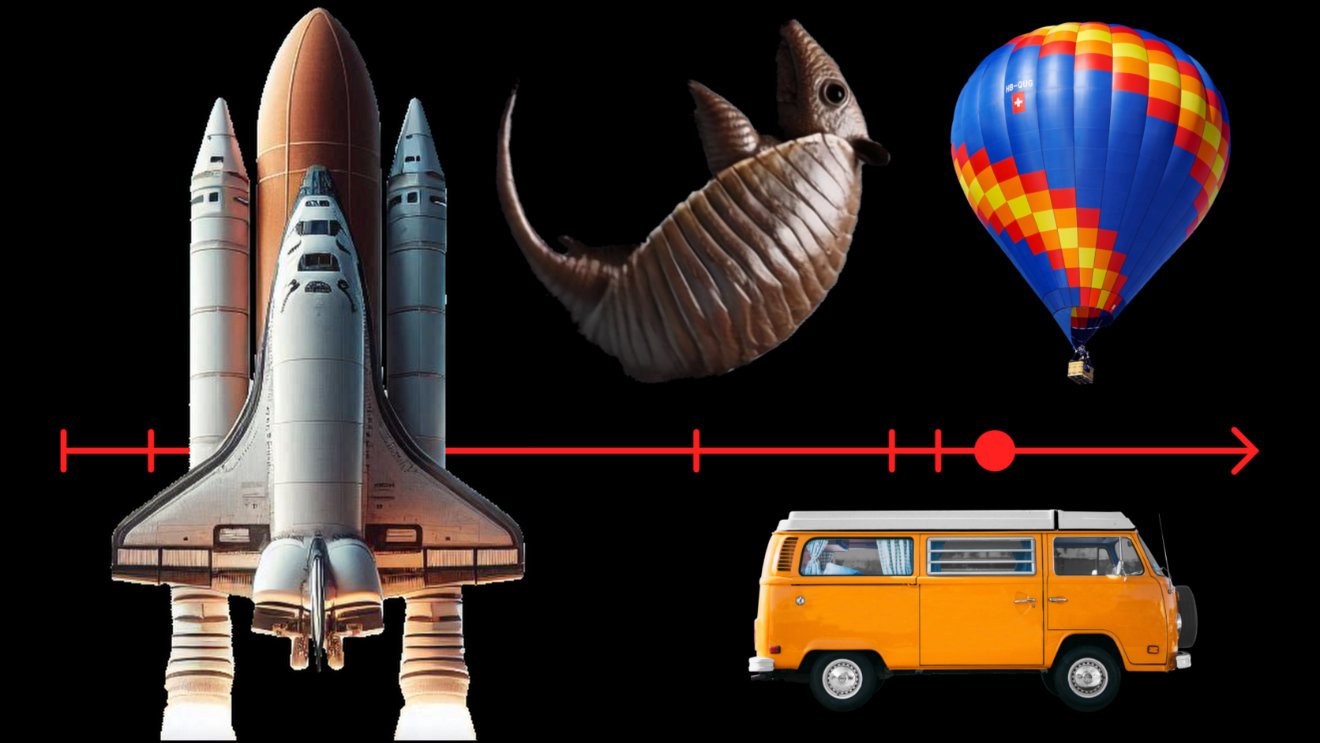

Just to be sure, the astronomer could use a clock to measure the frequency of the pulses. She could use an hourglass:

or a pocket watch:

or a digital timer:

or an atomic clock:

or even another pulsar, because, as I say, pulsars are good at keeping time:

But all these clocks – the hourglass, the pocket watch, the digital timer, the atomic clock, the other pulsar – are in the universe. They’re in the hypergraph. So if I apply the rules twice as fast, they too are evolving twice as fast: the sand is falling twice as fast, the pocket watch is ticking twice as fast, the digital timer is incrementing twice as fast, and the electrons in the atoms switch between energy levels that are twice the frequency. And that other pulsar? Well it, too, is, of course, pulsing twice as fast, from your God’s-eye perpective.

From the astronomer’s perspective, inside the hypergraph, no matter how she measures the frequency of the pulses, nothing changes.

The one clock she can’t use is the clock on your device.

She can’t perceive the speed of the pulses as measured by the clock on your device, because she can’t see the clock on your device. It isn’t in the hypergraph. It isn’t in her universe. In my astronomically over-simplified visualization, it doesn’t exist.

There is no giant clock in the sky.

When you look at my visualizations of the hypergraph, you need to get that clock on your device out of your mind. You need to get the space where you and I live out of your mind. You need to get the time where you and I evolve out of your mind.

All there is is the hypergraph.

It’s not in space, it is space, and everything in space, including the pulsar, the astronomer, and every clock she could possibly use.

All there is is the evolution of the hypergraph.

It doesn’t happen in time, it is time.

Emergent

You might not immediately see much difference between our old way of thinking about time and this new way of thinking about time.

But there is a difference.

Our old way of thinking requires us to make assumptions about time.

In our old way of thinking, just as we must assume three axes of space – scales along which we can measure what’s where...

...so we must assume an axis of time – a scale along which we can measure what happens when.

It doesn’t matter whether, like Newton, we assume an absolute scale along which we can measure what happens when according to a giant clock in the sky, or whether, like Einstein, we assume a relative scale along which we can measure what happens when according to a tiny clock in each and every reference frame.

Either way, we must assume an axis of time.

Our new way of thinking doesn’t require us to make any assumptions about time.

We need only posit the application of rules to the nodes and edges of the hypergraph, and time emerges.

Take another look at my visualization of the pulsar and the astronomer’s brain in the hypergraph. When I created this visualization, I didn’t assume an axis of time, all I did was apply rules to the nodes and edges of the hypergraph. Everything we think of as time – the spinning of the neutron star, the propagation of the beams of radiation through space, the perception of the pulses in the astronomer’s brain – emerges from these applications of rules to the nodes and edges of the hypergraph.

In pre-computational physics, we need to assume time.

In Wolfram Physics, we don’t.

Time emerges from the hypergraph.

The clue

One more thing.

Our simple insight, that the evolution of the hypergraph is time, gives us a clue, not just to the nature of time, but to the nature of the universe.

It’s a clue so profound that I’m only beginning to compute the consequences.

I’ll tell you what that clue is in the next article for The Last Theory.

—

References

- The canonical mass of a neutron star is 1.4 solar masses

- The mass of the Sun is 1.988416 × 1030 kg

- The mass of a neutron is 1.67492750056(85) × 10-27 kg

- So the number of neutrons in a neutron star, assuming neutron stars are made entirely of neutrons (which they’re not), is 1.4 × 1.988416 × 1030 kg / 1.67492750056(85) × 10-27 kg ~ 1057

Credits

- Pulsar animation by Michael Kramer licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

- Retina image by د.مصطفى الجزار licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0