Do you know what causality is?

If you do, let me know, because I’m not sure.

I’ve never come across a conception of causality that makes sense to me.

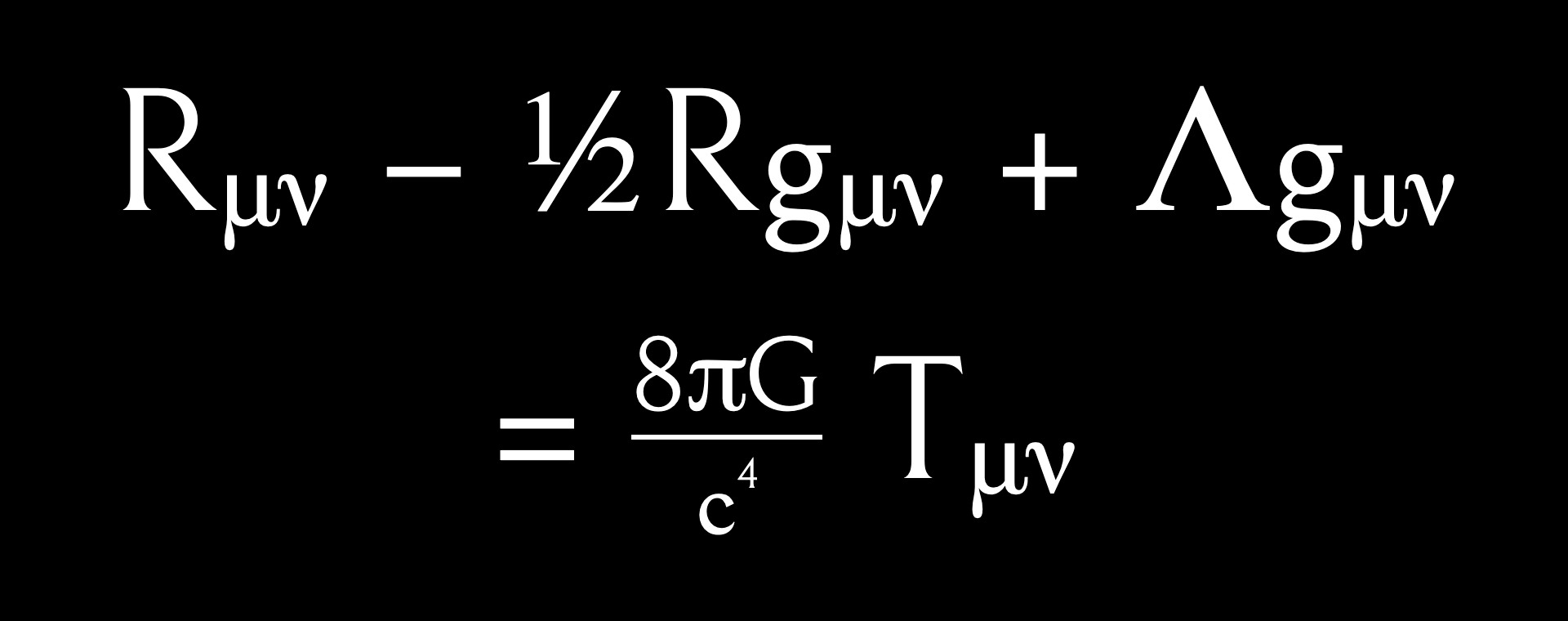

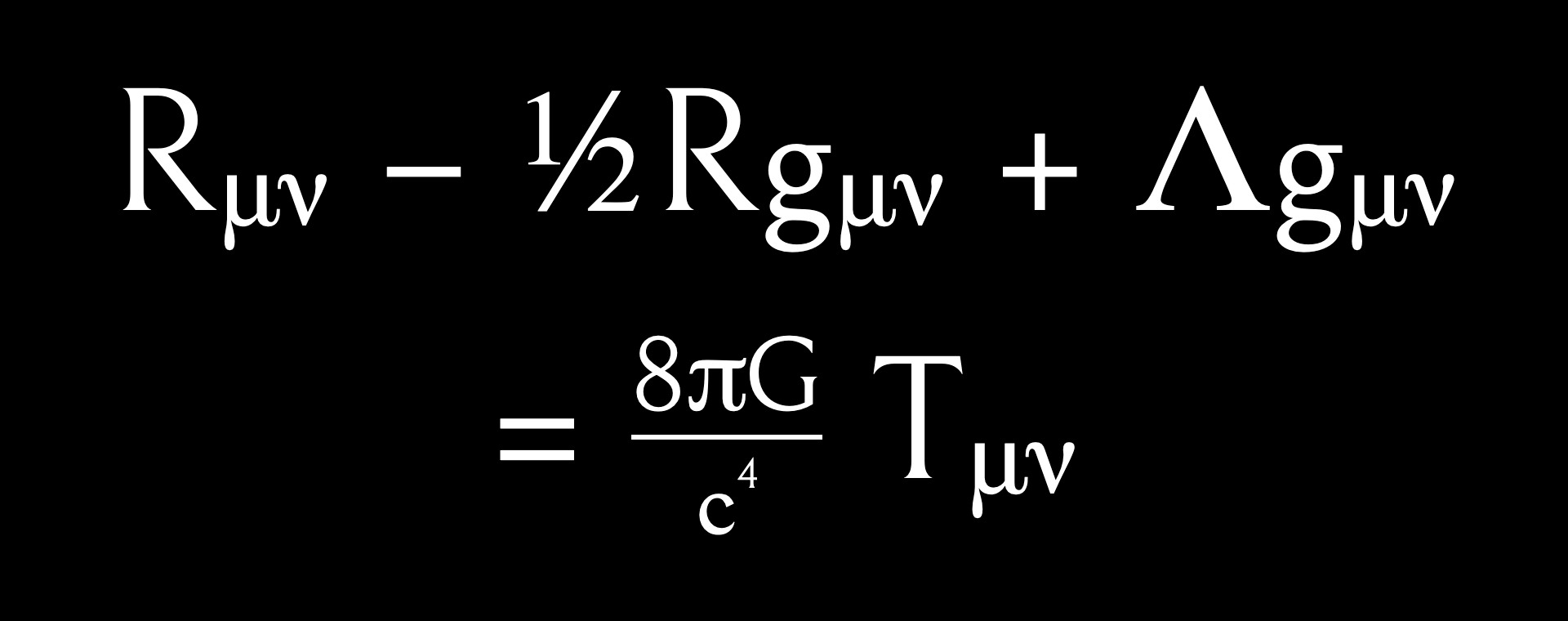

After all, our universe seems to follow simple equations like this one:

and there’s no mention of causality in these equations.

It makes me think that there’s no such thing as causality.

Unless...

Well, here’s the thing.

I’m no longer sure that our universe does follow these continuous equations.

I’m beginning to think that at the smallest scale, our universe might evolve through discrete computations.

If that turns out to be true, it allows for a limited conception of causality after all.

It’s causality, Jim, but not as we know it.

—

What is causality?

You might think that’s a silly question.

I mean, causality, it’s straightforward, isn’t it?

It’s when one thing causes another.

If I throw this ball, it flies through the air.

The motion of my hand causes the ball to move through the air.

That’s causality, right?

Well, sure, that gives us an idea of what we mean when we say the word “cause”, but I still haven’t said what causality is.

I confess that I find the concept of causality slippery.

Sure, if we think in the abstract, we can say things like:

- the cause must precede the effect;

- the cause must create the necessary conditions for the effect;

- the cause must increase the probability of the effect;

or, if we dare be less timid:

- the cause must necessitate the effect.

But the moment we try to apply the concept of causality to real phenomena, these abstractions prove meaningless.

Let me show you what I mean.

Cause → effect

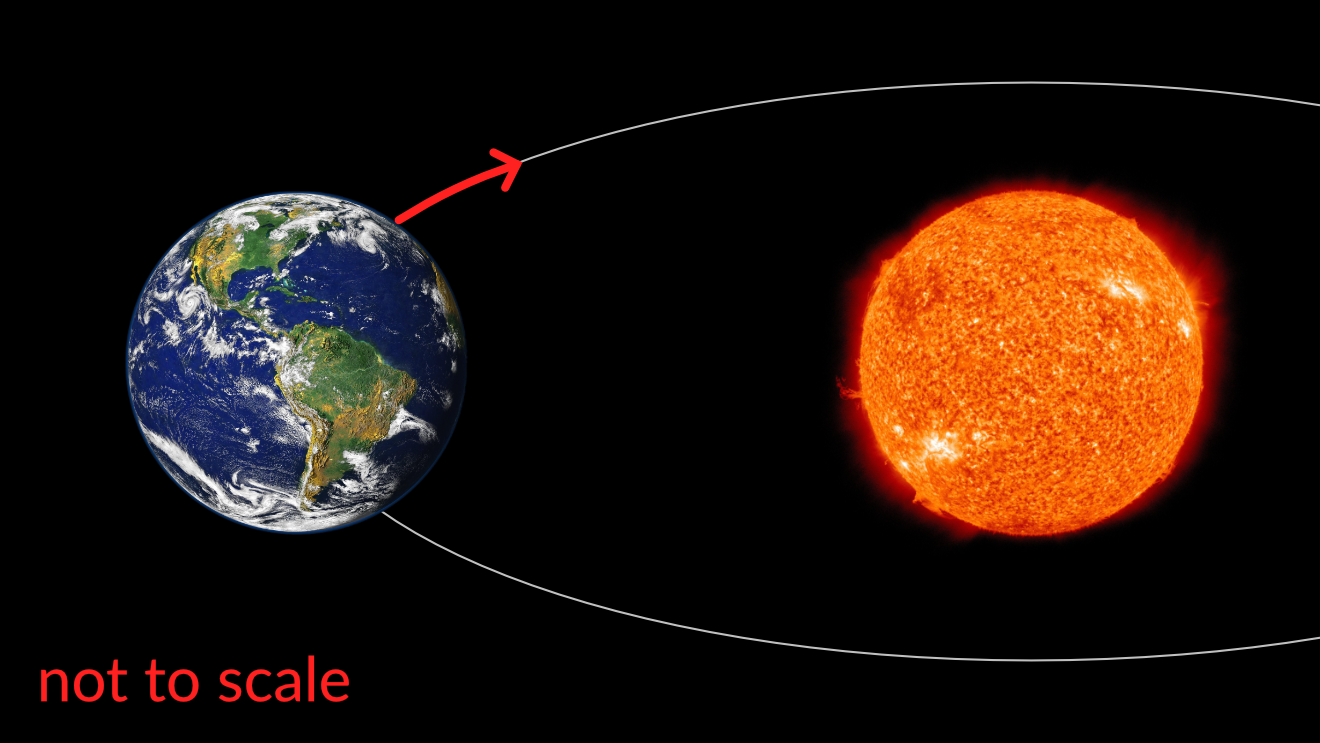

Take the orbit of the Earth around the Sun.

Even the Catholic Church now concedes that this is a real phenomenon.

Here’s an equation that describes the orbit of the Earth around the Sun rather precisely:

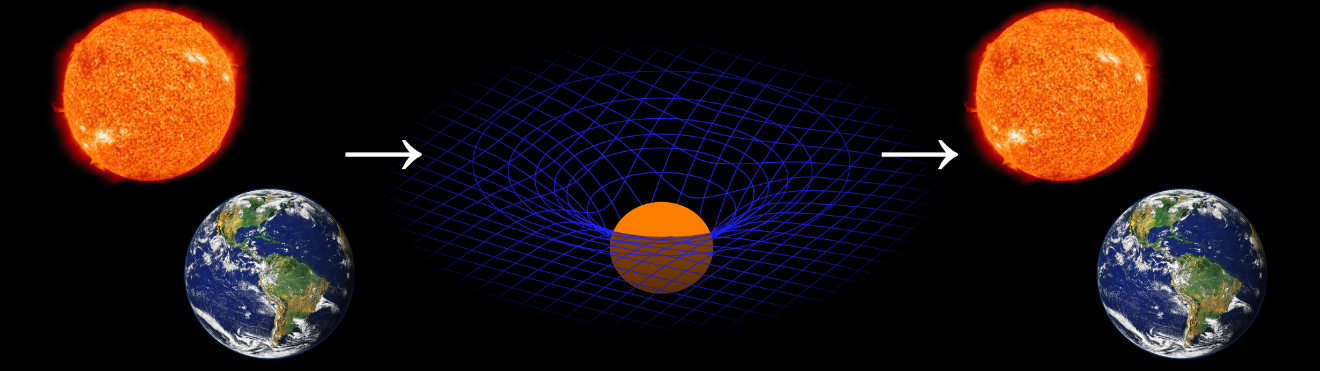

Einstein’s equations tell you everything you need to know about how the Sun, the Earth and the various other conglomerations of matter in the vicinity warp space and time in such a way that the Earth follows its slightly wobbly elliptical orbit around the Sun.

I’ll say that again.

That equation tells you everything you need to know.

So where’s the causality in this phenomenon?

Can we say that the Sun causes the Earth to move as it does?

Can we say that the Earth causes the Sun to move as it does?

Can we say that the Sun and the Earth cause the warping of space and time, and that the warping of space and time cause the motion of the Sun and the Earth?

Well, we could.

But any such statement about what causes what seems redundant, because, I’ll say it again, the equation tells you everything you need to know, and there’s no mention of causality in the equation.

↑

no mention of causality

These statements – about the Earth causing the Sun to move as it does or the Sun causing the Earth to move as it does – don’t even conform with our abstract ideas of causality.

Our most basic abstract idea of causality is that the cause must precede the effect.

Does the Sun precede the Earth? Does the Earth precede the Sun? These questions are meaningless.

Do the Sun and the Earth precede the warping of space and time? Does the warping of space and time precede the motion of the Sun and the Earth? Again, these questions are meaningless.

There’s no precedence. It all happens at the same time.

There’s no cause, no effect. Einstein’s equations don’t specify matter as the cause and motion as the effect, any more than they specify motion as the cause and matter as the effect.

Things aren’t looking good for causality.

Here we have a real phenomenon, the orbit of the Earth around the Sun, and there’s no role for causality.

One thing after another

Here’s my conjecture.

There’s no such thing as causality.

At least, there’s no such thing as causality in the common sense of the word, no such thing as the causality we invoke when we say that the motion of my hand causes the ball to move through the air.

Sure, when it comes to history, in all its chaos and complexity, you can talk about causality. You can write an essay about the “causes” of the First World War, if you really want to.

I’m not so sure how much sense such an essay can make. I tend to think that history is just one thing after another. But sure, the “causes” of the First World War, that makes some kind of sense.

But when it comes to physics – the kinds of phenomena, like the orbit of the Earth around the Sun, that can be described by an equation – there’s no place for causality.

I’ll say it one more time. Whether it’s Newton’s equations of gravitation and motion, Einstein’s equations for the warping of space and time, or whatever formulation might supercede these theories in future, the equations tell you everything you need to know.

Here’s the catch.

If you think that the universe evolves according to immutable laws of nature, rather than, say, divine intervention, occult forces or magic spells, then it’s difficult to argue that there’s a place for causality in history, any more than there’s a place for causality in physics.

If you think that the universe evolves according to immutable laws of nature, then the only difference between the orbit of the Earth around the Sun and the First World War is the chaos and the complexity.

(And the endless poetry.)

Physics and history are the same: just one thing after another.

Free will

If we think that the universe evolves according to immutable laws of nature, then why do we insist on causality?

Here’s another conjecture.

We insist on causality because we insist on free will.

It’s easy to look at the Sun and the Earth and accept that there’s no causality, it’s all just equations.

It’s more difficult where we ourselves are involved.

When I think about my throwing the ball, I place the emphasis on the I.

I decided to throw the ball.

Sure, the Sun and the Earth just follow the equations, but not me.

I’m different.

The Sun and the Earth have no choice, but I do.

I decided to throw the ball, but I could have decided not to throw it.

I have free will.

Sure, when it comes to inanimate objects like the Earth and the Sun, maybe it’s just equations, maybe there’s no place for causality.

But when it comes to me, well, I have free will, I decided to throw the ball, I caused the ball to fly through the air.

Our concept of causality comes from our concept of free will.

There’s only one problem with this line of reasoning:

There’s no such thing as free will.

The hard problem of consciousness

OK, I realize that by saying that there’s no such thing as free will, I’ve just lost half my audience.

There’s something I’ve noticed about free will:

No one over the age of 22 ever changes their mind about free will.

All sorts of people of all sorts of all ages change their minds about all sorts of things: about whether God exists, about whether to have children, about the best flavour of ice cream.

But if, at the age of 22, you still believe in free will, there’s nothing I can say that’ll change your mind.

Why do we find it so hard to accept that there might be no such thing as free will?

Part of the problem is that it feels like we have free will.

Actually, it’s deeper than that. Part of the problem is that it feels like anything at all to be ourselves.

This is the hard problem of consciousness.

I can’t tell you precisely how it feels to be me, but I can tell that it does feel like something.

If it didn’t feel like anything at all to be me – if I were an automaton rather than a conscious human – then it wouldn’t feel like I have free will.

If that were the case, it wouldn’t be so hard to accept that we humans, like the Sun and the Earth, just follow the equations, that we, like the rest of the universe, evolve according to immutable laws of nature, that there’s no need for a concept of causality.

I don’t have a solution to the hard problem of consciousness. I don’t know why it feels like something to be me. That’s why they call it the hard problem of consciousness: it’s a hard problem to solve.

But I do have an idea why, quite apart from the fact that it feels like we have free will, we find it so hard to accept that we might as bound by the immutable laws of nature as the Sun and the Earth.

The story of the universe

It goes back to the chaos and the complexity.

It’s difficult to overstate how much more chaotic and complex my throwing the ball is than the orbit of the Earth around the Sun.

Think about it.

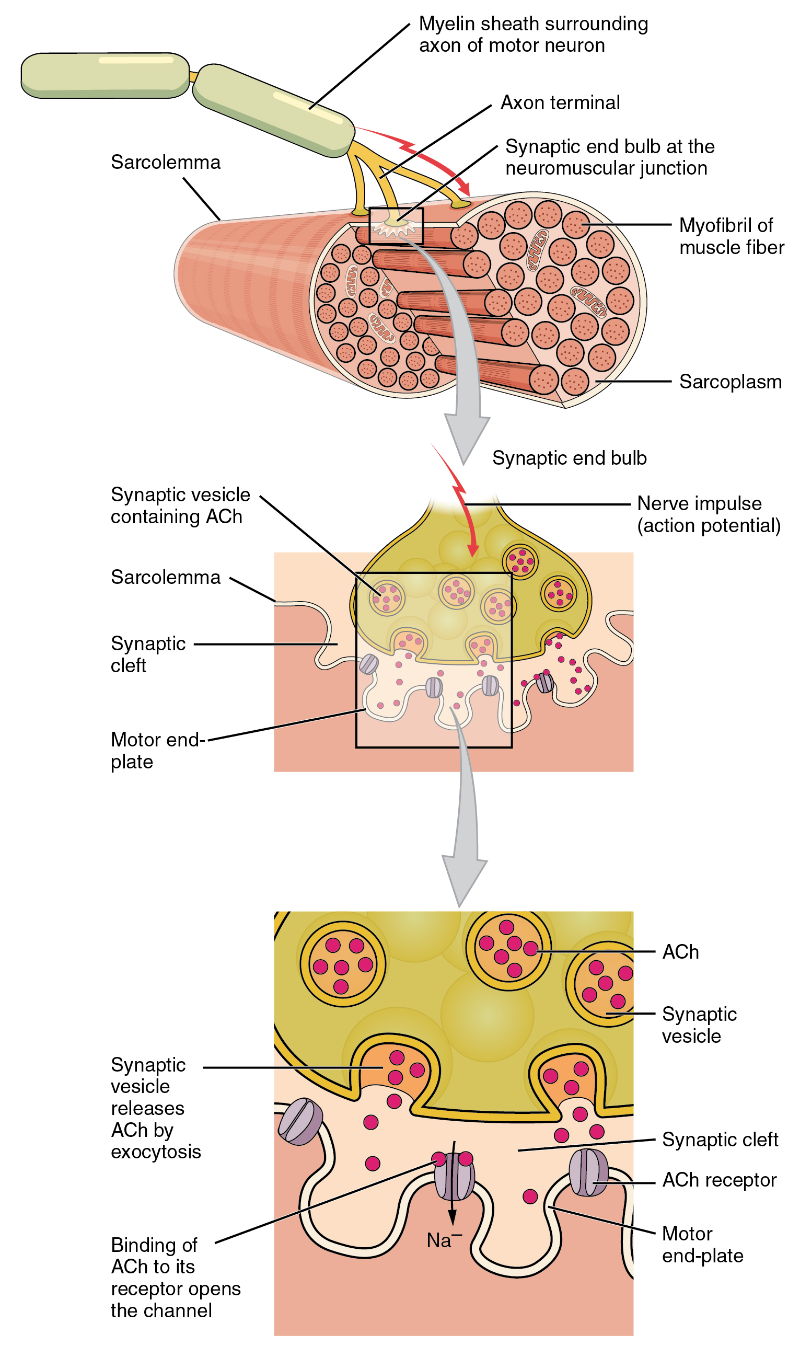

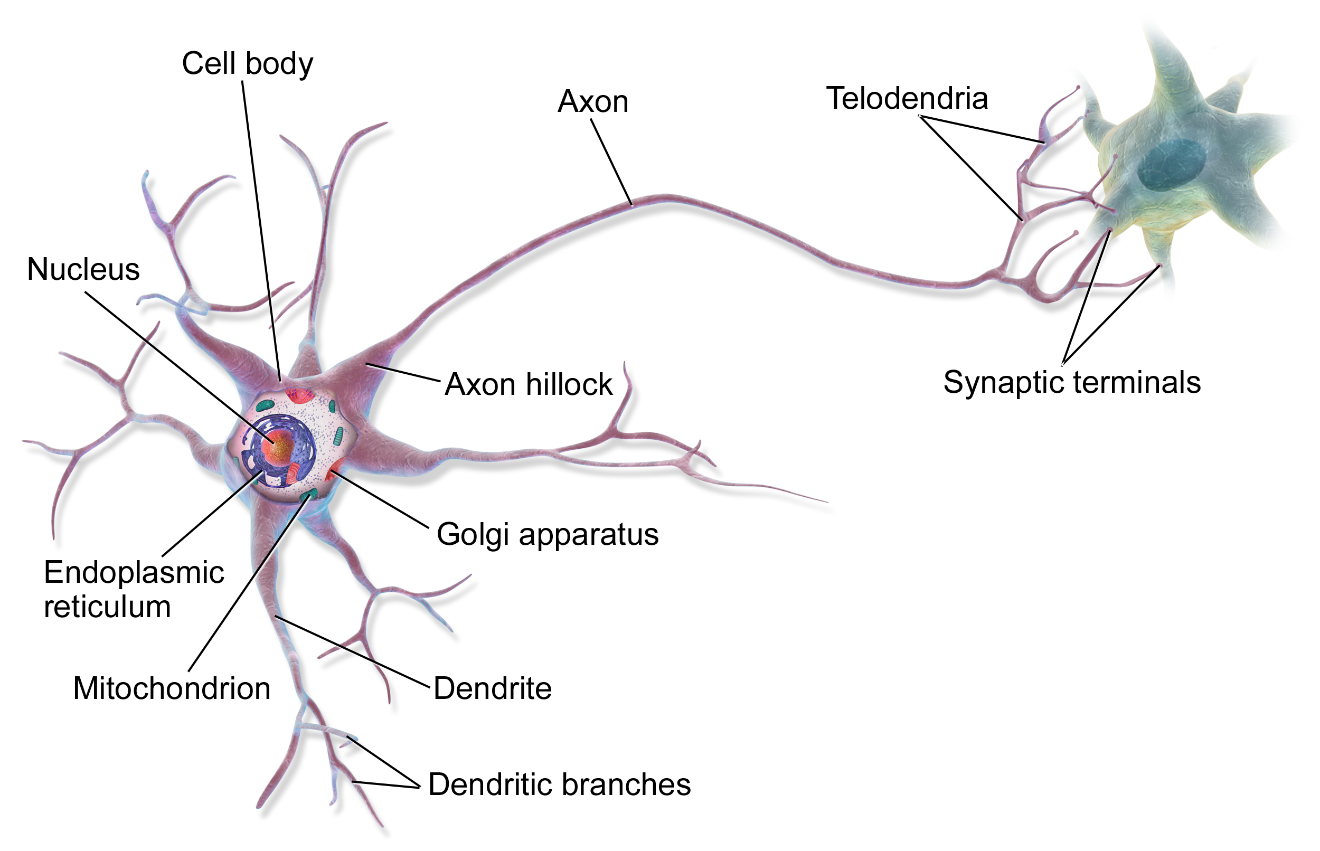

The mechanism by which my muscles contracted in the precise configuration required to move my hand in such a way as to throw the ball is not too complicated. Electrical impulses propagated along the nerves from my brain to my muscles; sodium and calcium ions were released into the muscle fibres; these fibres contracted.

Even here, it’s tempting to lapse into the language of causality: the electrical impulses caused the release of the sodium and calcium ions; the sodium and calcium ions caused the muscle fibres to contract. But here, at least, it’s not too hard to imagine that it all just follows from the biological pathways, which follow from the chemical reactions, which follow from the physical equations. Call it causality if you must, but its all just one thing after another.

Where we run into trouble is in tracing those electrical impulses back into my brain.

What was the mechanism by which the neurons in my brain fired in the precise configuration required to move my hand in such a way as to throw the ball?

That’s an astonishingly, ridiculously, impossibly complex question.

The answer of the free-will-believer – that I decided to throw the ball – explains nothing.

Any serious answer must address the following realities:

- when I recorded the video of this article, I threw the ball at the point at which I first mention throwing the ball, as seemed appropriate;

- when I wrote the article, I sought a simple, visual example of what we think of as causality that involved what we think of as free will;

- I originally thought of dropping a stone, but decided that it would be better if I threw a ball, since it’s a clearer demonstration of volition;

- I wrote this article because I wanted to tackle the question of what causality is, since it’s a natural question to arise from my previous article on causal invariance, as well as an essential question to answer ahead of my upcoming articles on the causal graph;

- I launched The Last Theory because I heard about Wolfram Physics from a friend, found it compelling, and took the opportunity to write about it and make videos about it as I explored it;

- I was well placed to do so because I’d spent half a lifetime reading physics, reading philosophy, writing books, writing code, creating simulations, creating visualizations and making movies;

- these predilections were made possible by the circumstances of my life, including the technologies of paper, computers and cameras, and the culture of education, enterprise and freedom;

- the civilization in which I find myself arrived at these technologies and this culture after thousands of years of exploration, commerce, persuasion and revolution;

- if the circumstances of my life made my reading, writing, coding and creating possible, my genes, too, predisposed me to these directions;

- my genes are an improbable combination of nucleotides, in spirals that have evolved over billions of years of life on Earth, influenced by an unimaginable number of incidents in which organisms with different combinations of nucleotides thrived or wasted away;

- these nucleotides are made up of atoms, formed in stars and scattered through space through supernova explosions, made up of particles, formed in the first few seconds of the universe.

I don’t mean to be grandiose, but the story of how I came to throw the ball is the story of the universe.

Deus ex machina

It’s easy to accept that the parabolic path of the ball through the air follows simple equations.

It’s harder to accept that the billions of years of chaos and complexity that led, through particles, atoms, nucleotides, genes, evolution, proteins and neurons, not to mention all human history, to my throwing the ball also follows simple equations.

I don’t blame you if you’re tempted to collapse this low-level chaos and complexity into a more harmonious, high-level concept, such as God, or the human soul, or free will.

And if you do, I can see how the concept of causality might come along for the ride. God decrees. Human souls commit acts of virtue and vice. I, in an exercise of free will, decide.

But if you hold out hope that there might be equations that tell you everything you need to know about how the universe evolves, without resort to any such deus ex machina, then you might be inclined to conclude that there’s no such thing as causality.

Not your grandmother’s causality

And yet, I do think there’s a role for causality in physics.

I wouldn’t be writing articles about causal invariance and causal graphs if I didn’t.

There is such a thing as causality. It just ain’t what you think it is.

In this article, I’ve been talking about equations, like this one, in which there’s no role for causality:

Lately, however, I’ve been beginning to wonder whether such continuous equations, though they undoubtedly capture the behaviour of our universe at a large scale, might not be mere approximations to a discrete, computational model at a small scale.

Wolfram Physics postulates that the universe might be modeled by a hypergraph of nodes and edges that evolves over time through the repeated application of rules.

In this discrete, computational model of space and time, physics is literally just one thing after another.

There are no God-like equations that trace the simple, stable orbit of the Earth around the Sun over billions of years... at least, not at the smallest scale, not at the scale of the nodes and edges of the hypergraph.

There’s just one application of a rule to the hypergraph, then another application of a rule to the hypergraph, then another application of a rule to the hypergraph... and all the chaos and complexity that arises from these simple applications of a rule to the hypergraph.

And it’s here, in these applications of a rule to the hypergraph, that we uncover a role for causality after all.

If one application of a rule to the hypergraph plays a part in creating the necessary conditions for another application of a rule to the hypergraph, we can say that there’s a causal connection between those two applications of a rule to the hypergraph.

It’s not much.

I’m not saying that one application of a rule to the hypergraph causes the other application of a rule to the hypergraph.

I’m just saying that there’s a causal connection between them.

This is not your grandmother’s causality.

It turns out, though, that this humbler concept of causal connection is crucial to our understanding of universe according to the Wolfram model.

It takes us to the causal graph, and that takes us to special relativity, general relativity and quantum mechanics.

There’s no deus ex machina here: no God, no human soul, no free will.

But if you’re willing to accept that causality ain’t what you think it is, if you’re willing to embrace this humbler concept of causal connection, well, we can go a long way with that.

—

Images:

- Gravitation space source reproduced under CC0 1.0

- DC-1914-27-d-Sarajevo-cropped public domain

- Australian infantry small box respirators Ypres 1917 public domain

- Neuron transmission by BruceBlaus licensed under CC BY 3.0

- Muscle innervation by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Muscle contraction by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0